“We long to praise you, though we are burdened by our mortality. Though we are conscious of sin, we long to praise you. You stir in us the desire to praise you. Our delight is to praise you. For you have so made us that we long for you, and our heart is restless until it rests in you.” (Book 1, Chapter 1, St. Augustine’s Confessions)

Saint Augustine of Hippo, that great 4th century Latin Father, the Doctor of Grace, was my first real favorite saint after St. Joseph, my 6th grade choice for my Confirmation name. At the age of 16, I traveled across Canada from Ottawa to Vancouver on a Greyhound bus and read the Confessions. My traveling buddy most likely thought I was strange, but he did not ask questions.

I could not believe I was reading the personal life story of a human being from the 4th century and that what he shared made perfect sense to me. I loved his candor, his devotion, and the beautiful way the entire book was addressed to Our Lord. I also loved the way he integrated the Scriptures into his prose. My long journey across the flat Canadian Prairies was made tolerable with Saint Augustine by my side.

Except in short passages here and there, I had not re-read the Confessions since that young age. With great delight I recently rediscovered the pious vulnerability that is manifest on every page. With even greater delight I could see how his writings reveal the inner multiplicity of the human person. In this article I want to zoom in on Books 7 and 8 where he describes his conversion experience.

A word about translations

Translations make all the difference in my opinion and translators must strike a balance between being technically accurate, in this case to the Latin, being readable in English, and capturing the spirit of what the author is trying to convey.

I am fairly sure I was reading the Image Classics translation when I was 16. That translation, if I am right, was done by Frank Sheed in 1942 and was somewhat formal but readable. I was a precocious kid and loved it, but I’m willing to bet the average 16-year-old, and maybe a few adults, might not agree with me.

I recently re-read passages from a much older version, 1886 in fact, translated by J. G. Pilkington. This translation was interesting but didn’t lend itself terribly to the modern reader. I used this translation on my recent appearance on the Interior Integration for Catholics podcast dedicated to Saint Augustine.

Since then, I wanted to find a more modern translation that might make Saint Augustine’s experience really come alive. I acquired Maria Boulding’s much recommended 2002 translation. She was a cloistered Benedictine nun, and many people find her translation laudable but for some reason I personally found it less helpful than even the older translations. It just didn’t speak to me.

In the end though, I fell in love with Fr. Benignus O’Rourke’s 2013 translation which in my humble opinion is the best – poetic, readable and powerful. Fr. Ben is an Augustinian friar, and it is his translation which I decided to use for this article.

St. Augustine’s conversion

In Book 7, we read about St. Augustine’s intellectual conversion, which is more of an assent of the will. He is moved by the conversion of his friend, and he reads about St. Anthony of the Desert. At this point Christianity makes sense to him, he wants to live a life that is chaste and ordered to God, but he realizes he cannot reform his will by intellect alone and that he needs grace.

In Book 8 we see a real conversion of the heart where he surrenders to God with an intense vulnerability. Although very difficult, he finally chooses, at a heart level, to turn away from his past problematic behaviors. In this way, Augustine gives primacy to the heart, not to sentimentality, but to a deep affective shift toward God, a real choice to reform his will. He moves from wallowing in pain, regret, and shame to renewed self-energy with a sense of clarity, purpose, openness, and freedom.

A saint’s struggle with addiction

Saint Augustine says that the enemy has “chained his will” and that there is a “chain to bind me” that has made his will perverted. His lust moved from a habit to a “necessity.”

This really speaks to the reality of addiction. Once addicted, a person behaves compulsively or out of a sense of necessity. His new “will” which is spiritual and delights in God was initially not strong enough to oppose the addicted “will” which is “under the power of the sensual self.” This really speaks to the inner conflict present in the addicted person. The self-led manager part is in a losing conflict with the desperate firefighter part.

These were the links that formed what I call my chain,

and this chain held me in iron bondage.

The new will which had begun to stir within me,

the will to take delight in you

and to serve you freely, my God, our only true happiness,

this will was not yet strong enough to win over the old one,

hardened as it was by habit.

So within me were two wills, one old, one new;

one under the power of my sensual self,

the other ruled by the spirit.

They were in conflict.

And the conflict tore me apart.

When the Doctor of Grace describes having two wills in conflict with each other, I do not believe he means to imply that a human being has two wills at an ontological level. He is expressing the phenomenological experience of parts in conflict with each other. But here we hear him describe his emerging “true self” which is no longer allied with “the desires of the flesh” but instead saw itself as a victim.

Dissociation results from lack of integration

Augustine speaks about carrying a “burden of the world” that he is unable to let go of. He describes himself as “one wanting to wake out of sleep” but “overcome with heaviness.” He knows that it is better to be “alert” and to “surrender to your love” but he is unable to do so. He describes the inmost self as wanting to turn to God but “another law” was holding him “prisoner.” Augustine realizes that only by the grace of God would he be freed from this “bondage.”

It was no use that in my inner deeper self

I delighted in your law

when another law held sway in my body

and fought against the law in my mind,

holding me prisoner to the rule of sin in my unspiritual self.

When parts are dissociated from each other, when parts are operating independently of the inmost self, we say there is a lack of integration. The beginning antidote to this problem is to un-blend from these parts and gain a conscious awareness of them. We must get enough “distance” from these parts to be able to truly see them and possibly work with them toward change.

Seeing one’s parts

Saint Augustine talks of standing “naked before my own eyes” and seeing himself clearly. This speaks to an un-blending where the inmost self can connect and see the part.

This dissociated part does not want to face losing its coping mechanisms which in this case includes sexual behaviors. The inmost self offers something greater, real wings, and real freedom, but the part still resists and is afraid of letting go of its burden. The chastising voice in the following passage sounds very much like an exasperated manager part speaking to a desperate firefighter part.

But the time had now come

when I stood naked before my own eyes,

while conscience rebuked me within:

‘Where now is your glib tongue?

You used to say that you would not shed

the baggage of your empty life

for a truth that was not proved?

But look, the truth is now certain

and you still carry your baggage,

while here are others

who have traded their burdens for wings.

Nor did they exhaust themselves

in their search for truth.

Neither did they spend ten years or more

making up their minds!’

Facing inner struggles

Augustine has a part, I believe a spiritual part, angry at his “soul” (perhaps we can understand “soul” here as several burdened parts of his self-system) for not following God. The spiritual part is angry at the other part who “refused” to enter a relationship with God and “hung back” because it feared losing its “vile habits.”

Firefighter parts often refuse to let go of their habits because these are well practiced means of coping – they protect against difficult feelings and situations.

The soul feared as much as death itself

my need to stop the flow of vile habits,

which habits were themselves

a kind of rotting away of life.

Saint Augustine’s “inner self was divided against itself” which describes the inner conflict within the self-system. He describes this inner turmoil as a “storm.” Saint Augustine then goes into the garden where he could be alone and engage “the fierce struggle I was having with myself until it was resolved.”

I believe the garden represents his inner world, his unconscious mind, where he must wrestle with this unresolved inner conflict. In parts work, we help clients access those inner worlds to resolve trauma by accessing otherwise repressed parts of the self-system in need of help.

Augustine feels like he is losing his sanity or dying. He un-blends from his parts as he says, “I was aware of the evil that held me. I was unaware of the good that was about to be born in me.” His inmost self, as yet unknown to him, was beginning to emerge. He struggles, however, with his own inability to take action.

In this case his “soul,” or a group of resistant parts, refuses to do the thing he desired it to do. Saint Augustine says “Yet it does not obey its own command” which really means one part in in opposition to either the inmost self or a self-led manager part. Either way, he powerfully describes his own inner turmoil.

Experiencing polarizations

Saint Augustine continues to notice his ambivalence around change when he says, “So it is not so absurd that the will can will something partly, yet partly will not do it.” He even goes on to say, “Thus there are in us two wills. Neither is whole. Each possesses what the other lacks.” As mentioned above, he does not truly mean that the human has two wills; he is merely trying to explain his experience of parts in opposition to each other.

Saint Augustine then discusses how he tried to fix himself rather than rely on God. When he tried to exercise his will toward the good, he noticed that he could not do it. “I was the one who willed it, and I was the one who rejected it. I, and I alone. But I neither fully willed it, nor fully rejected it.”

He expresses his distress powerfully “So I was in conflict with myself. I was falling to pieces.” Again, this is a compelling description of the pain of interior dis-integration and an IFS polarization.

Augustine attributes this inner division to sin. He acknowledges that the experience is more than just two parts, but many. “For I was a son of Adam. If then there were as many different natures in us as there are wills in conflict, we should have not two but many.” And yet he avoids dualism and says we have one soul with opposing wills, and sometimes both wills have an evil desire.

In the same way a person may also have conflicting “good” wills. Essentially, he describes the inner complexity of being a human person made with inner multiplicity. But at this time in his life, he becomes acutely conscious of how his parts are at war and how this lack of inner harmony is torturing him.

They are in conflict until the person chooses one course,

and applies the will,

which has been split in many parts,

to one purpose. So too, when the delights of eternity draw us upwards

and the delights of worldly pleasures drag us down,

it is the same soul that wills both,

but pursues neither wholeheartedly.

So the soul is torn apart and suffers,

since love of truth proposes one way,

but the force of habit will not surrender.

Saint Augustine blames himself and describes himself as in chains. But he also discovers his inmost self, “in the hidden places of my being” where the Lord is “kept close to me with stern compassion.” Interestingly, the self-system takes on fear and shame as a protective move while the inmost self is gaining more energy.

In my heart I kept saying,

‘Let it be now. Now is the moment.’

And in saying it, I was almost there.

I would almost reach a decision,

but I kept falling short.

Saint Augustine literally personifies his parts that were fighting back against the inmost self.

Trifles held me back, insignificant trifles.

Empty toys, my old, old friends,

pulled softly at my garment of flesh and whispered,

‘Are you sending us away?’

And, ‘Will we from this moment

never ever again be your companions?

From this moment will you never be allowed

to do this or that ever again?’

As I tried to move on,

they secretly tugged at me to make me look back.

It was just enough to slow me down.

For I could not tear myself away, nor shake them off.

His reactive parts were taunting him:

‘Do you think you can live without these things?’ But by now the voice was very faint. My eyes were looking elsewhere. My face was set in the direction where I was fearful of going.

The inmost self arises

Gradually, the inmost self gains energy as his “face” turns more to God, and another figure, which he calls Chastity, appears. It is possible that Chastity could be understood as a beautiful unblended unburdened self-led part, but I think Chastity could also represent the inmost self.

Chastity brings calm to his fearful system. Chastity is described as “a mother of countless children” who brings joy and encouragement. The children around Chastity are of different ages, some even widows and old women – they could be understood as the many exiles lost to Augustine’s conscious mind. Chastity tells him not to be afraid, and to rely on God rather than on his own efforts. Chastity tells him that God will “hold” you and “He will heal you.” Saint Augustine relays the message, the call to conscience really, of Chastity:

Close your ears against the whisperings

of your unspiritual self,

so that they may be silenced.

They tell you of things that delight you,

but they are at odds

with the law of the Lord your God.’

To which Saint Augustine reflects:

This was the conflict going on in my heart,

a conflict in the depths of my heart

with myself and against myself.

At this point the good Doctor of Grace opens “the eyes of my heart” and there was a “flood of tears.” This cathartic moment for Saint Augustine was the beginning of his deep heart-felt affective turn toward God.

Somehow I flung myself down beneath a fig tree,

and let the tears flow.

They flowed in torrents from my eyes.

And they were an acceptable sacrifice to you.

This was surely a moment of profound repentance, but he still felt guilty and fearful of God’s anger. It is at this point that a small child appears in his mind’s eye telling him to “pick it up and read, pick it up and read.” Augustine interprets this as a message from God to open the Bible at random and he read a passage from Saint Paul’s Letter to the Romans, Chapter 13:

“Let us live decently as in the daytime,

not in carousing and drunkenness,

not in sexual immorality and sensuality,

not in discord and jealousy.

Instead put on the Lord Jesus Christ,

And make no provision for the flesh

to arouse its desires.”

To which he responds:

I did not wish to read further.

There was no need.

For in an instant,

as I came to the end of the sentence,

it was as if a light of certainty flooded my heart

and the dark shadows of doubt were dispelled.

This moment is a powerful unburdening for Saint Augustine where he was able to let go of the attachments of his past life and “put on the Lord Jesus Christ.” This tear-filled unburdening leads to a deep sense of inner calm. Saint Augustine then goes to his mother, Saint Monica, and she rejoices when she hears about his newfound experience of faith. The Saint then thanks God for this powerfully spiritual and relational experience with his mother.

’You turned her sadness into joy,’ into a joy far deeper than she had ever hoped for, far more tender and chaste than she had ever envisaged.

And here ends Book 8 which so beautifully and movingly describes a man’s movement from inner turmoil and chaos to interior calm, peace, and joy.

Obviously, it doesn’t follow a perfect IFS protocol, we don’t for example see the old parts adopting new roles in his self-system. However, in it we see a major inner conflict causing a great deal of emotional distress, multiple interior parts at play, the emergence of the inmost self, and an unburdening that involves a profound emotional release. We also see a fair bit of relationality as he and his friend Alypius experience a parallel conversion, and we see the renewed bond with his mother.

Time for Personal Reflection:

I invite you to a moment of recollection. This is a prayerful calling to mind of all your parts, becoming aware of the inmost self, our deep spiritual center, and opening of your heart to God’s presence.

As your parts rest in a kind of gentle internal quiet, notice your body relax, your shoulders drop, and your face soften. As your breathing both deepens and slows, you become more aware of that deep spiritual center, your inmost self.

Notice how calm and restful that feels. Notice the presence of Jesus, the Word, who is Himself the perfect icon of the Father. Notice the presence of the Holy Spirit, the Comforter, whose love flows from the Father, through the Son, and into your heart.

Allow yourself to rest in that beautiful and perfect love that comes from our God.

Create a space inside to notice and welcome any parts that remain attached to unhealthy or problematic desires, attachments, behaviors, or activities. Without judgment, allow yourself to see them, to really see them. What are they trying to protect you from? What perceived good are they seeking?

Maybe within your system there is a mother-figure like Saint Augustine’s Chastity. She has many children, and they are free and joyful. She is calling all your parts into this space of new life.

What is holding your parts back?

What secret pain are your parts carrying?

Open the eyes of your heart and allow yourself to hold this pain.

Perhaps this could be a moment of tears, a moment of repentance, and a moment of release.

Allow yourself to take in any new sense of freedom you may experience. Notice the joy that comes with that. Share this joy with someone you love.

As we celebrate the Resurrection of Jesus and the salvation of our souls, let us allow His love to expand in our hearts, let us grow in love for God, for the Holy Trinity, for the Cross, for the Eucharist. Let us grow in healthy and ordered love for all the parts of our self-system, and then let us grow in true love, generous self-sacrifice, and service for others.

May God bless you on your journey this week!

Resources:

If you’re interested to learn more, here are a few resources you might want to check out:

The best (imo), more poetic translation of the Confessions is by O’Rourke, Ben. (2013) Confessions: St Augustine. London: Darton, Longman and Todd.

Other translations:

- Pilkington, J.G. (trans.) (1886) Augustine of Hippo, “The Confessions of St. Augustin,” in The Confessions and Letters of St. Augustin with a Sketch of His Life and Work, ed. Philip Schaff, trans. J. G. Pilkington, vol. 1, A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, First Series. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company.

- Boulding, Maria. (2002) Confessions: St. Augustine. New York: New City Press.

Video:

- Here is a seven minute video clip of the conversion of Saint Augustine. It doesn’t convey the nuances of inner multiplicity, but it is nevertheless a beautiful moment:

- Bishop Robert Barron provides a fairly detailed synopsis of the life and teachings of Saint Augustine in this hour-long video.

- A 10-minute helpful video synopsis by a Franciscan (Breaking in the Habit):

Christ is Among us!

Dr. Gerry Crete is the author of Litanies of the Heart: Relieving Post-traumatic Stress and Calming Anxiety Through Healing Our Parts which is published by Sophia Institute Press. He is the founder of Transfiguration Counseling and Coaching, Transfiguration Life, and co-founder of Souls and Hearts.

###

Learn more about your inner system, your parts, and your inmost self

During the Foundation Year of the Resilient Catholics Community, our members begin to learn about their own system and parts. The goal? To be able to love God, others, and yourself more fully and more joyfully. Our 10th cohort, named after St. Jerome, will open in just two weeks on June 1 for new applications.

Join hundreds of other faithful Catholics on this journey of human formation, informed by Internal Family Systems and grounded in a Catholic understanding of the human heart. Learn more.

A special invitation for Catholic formators

For the first time, Souls & Hearts will be hosting an in-person retreat just for Catholic formators. Spiritual directors, therapists, priests, coaches, or any other Catholics who is responsible for professionally forming someone else are invited to experience this human formation work in person in Indianapolis this August.

Get the details on our Formation for Formators retreat landing page here or watch this video here. You don’t need to be a member of our community to attend this retreat.

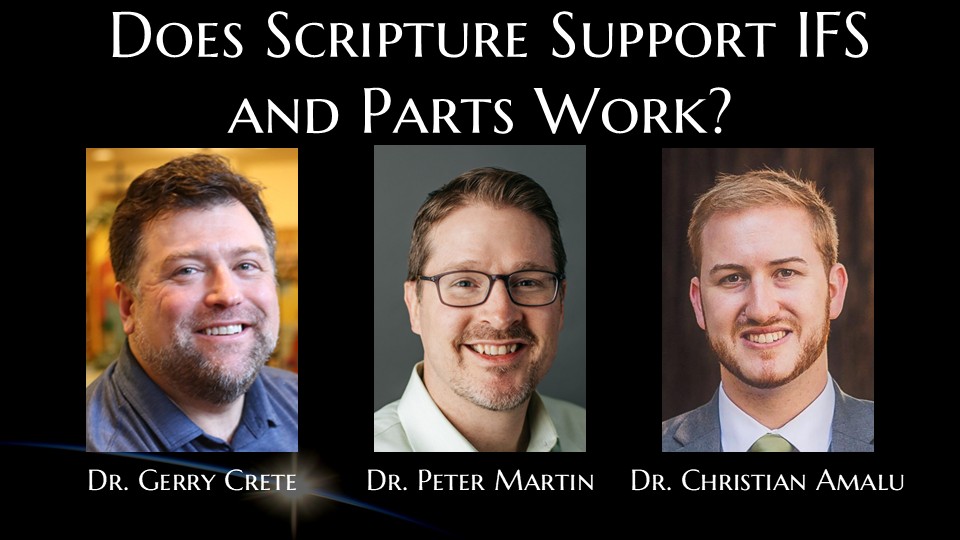

Check out Dr. Gerry on episode 166 of the IIC podcast: Can IFS and Parts Work Be Catholic? Listening to Scripture

Catholic psychologist Christian Amalu makes his debut on the IIC podcast as part of a great cast including Dr. Gerry and Dr. Peter Martin, as we begin a very specific focus on the Catholic roots of parts work, grounding parts work and IFS in an authentically Catholic anthropology. Join us for episode 166 Video Audio, here is the description:

Internal Family Systems is extremely popular not only as a therapy model, but as a way of making sense of our inner experience in daily life. IFS does not have specifically Catholic origins. But can there be a way of understanding parts work and systems thinking and harmonizing them with an authentically Catholic understanding of the human person? Dr. Christian Amalu, Dr. Peter Martin, Dr. Gerry Crete, and Dr. Peter Malinoski explore that question in these next episodes, starting with Sacred Scripture. What evidence can be found in the Bible to support the major tenets of IFS? How might IFS be understood through a Catholic lens? Join us for a tour of Scripture to answer these questions, with an experiential exercise as well.

Dr. Peter on the air with Josh Bach on the Belt of Truth podcast

In episode 136 of the Belt of Truth podcast titled The Silent Killer Who Stalks You from Inside, host Josh Bach talks with Dr. Peter about the “Silent Killer” that often goes unnoticed but affects countless men in the Church today. Together, they unpack how this hidden struggle impacts your relationship with God, your family, and your ability to lead with clarity and conviction. Dr. Peter shares how to recognize the signs in yourself and others—and offers practical, faith-rooted tools to fight back.

This episode hearkens back to episode 37 of the IIC podcast, expanding on that material, and taking it in new directions.